To those who lament the lack of movie stars in motion pictures, “Duplicity” offers solace.

Presently, Hollywood showcases actors of varying talents; what it doesn’t have on a consistent basis is silver screen icons. There are a plethora of good actors who hold our attention, surely, but far too many seem to favor self-indulgent and disconnected parts. Bankable names like Russell Crowe, Johnny Depp and Christian Bale choose roles where they almost exclusively portray loners, apparently finding solace in their character’s insularity and by losing themselves in costumes, accents and affectations. Powerful but distant, their detachment makes them feel small and isolated. There are thespians, fine artisans such as Philip Seymour Hoffman or Hillary Swank, who, bluntly, just don‘t radiate that “It” quality. And we’re encumbered with another generation of headshot pretty, vacant line readers; while that may be no different than the age of the studio contracts, it doesn’t alter the perception that they are merely wisps of space. Animation and special effects have nudged out, if not supplanted in many instances, live actors, both the gifted and the rubbish.

Perhaps nowhere has this dearth of magnetism been more telling than in romanticism because those box-office behemoths are just too comfortable playing the emotionally unavailable. Has Crowe ever cuddled on-screen? Has Depp ever swept a paramour off her feet? Has Bale ever swooned? It seems they’re too laden with breast plates and scissor hands for a little slap and tickle. With A-List actresses summarily jilted, it’s left to foreign flicks like “Priceless” or independent films such as “Milk” or even animation to provide the spark. It is telling that “WALL-E” was one of 2008’s most meaningful expositions on intimacy. It’s gotten so desperate that it can’t be too long until lesser lights attempt a computer-generated romance; coming this autumn, “PS, CGI Love You.”

In “Duplicity,“ Julia Roberts and Clive Owen exemplify not only the essence of being a movie star; they show self-indulgent SAG sack superstars how to bring sexy back. In his follow-up to the fabulous “Michael Clayton,” director and writer Tony Gilroy returns to the rubric of corporate intrigue through a lighter prism with Roberts and Owen as CIA and MI6 operatives who become lovers, retire from government spying, and enter the nefarious domain of corporate espionage by working for competing cutthroat multinational cosmetics companies. A byzantine plot trundles in a circuitous route, leaping back and forth through the last six years, skipping across continents. And while the film never flags, the labyrinthine machinations deviate from what makes “Duplicity” so much fun: the unforced chemistry from two scintillating performers. Through all of the plot twists and story subterfuge, Roberts and Owen deliver performances that accrete seamlessly as they let fly with sharp, flirtatious repartee that harkens to an age when witty verbal jousts between besotted equals were commonplace.

Roberts radiates the supreme confidence of a Tinseltown pro in her turn as the Claire Stenwick. With a twinkle in her eye, she has a certain Rosalind Russell vibe when swatting away Owen‘s chat up lines, or feeding him one of her own. Owen cleans up quite nicely for this film. In recent years, he‘s carved out a terrific resume in such films as “Sin City,” “Children of Men” and “Shoot ‘Em Up,” where he carried a perpetual seven o‘clock shadow like it was a trusty six shooter. But with smooth, high cheekbones shading his face like a single bruise on an apple, a clean-shaven Owen generates a stellar comic technique as Ray Koval. Wearing button down shirts even when on vacation, he looks like the dapper stud in the Lancôme cologne ads. (Before this film, if he was being paid in scents, it would have been British Sterling.)

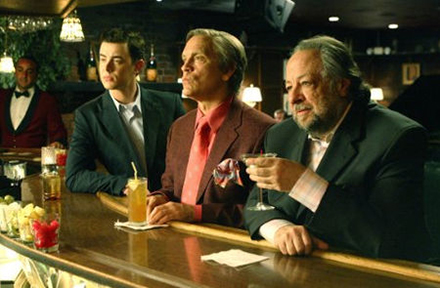

Gilroy casts the additional, secondary roles with astute choices. Tom Wilkinson is eerie disquiet as Howard Tully, the paranoid conglomerate CEO. Wilkinson is wickedly adept at finding the unnerving in a normal moment. As his rival, Richard Garsik, a snarling Paul Giamatti continues to construct the supporting actor as All-Star relief pitcher, a Mad Hungarian of frothy interjections and ruthless maliciousness. Further fine actors such as Denis O’Hare and Thomas McCarthy make up a notable “Michael Clayton” ensemble.

But “Duplicity” is best when focused on the pulchritudinous pair bonding with a terrific alchemy and it is this relationship which fomented my earlier (perhaps too) curmudgeonly rhetoric. Roberts and Owen simply provide a dwindling presence that makes going to movies so wondrous. Sometimes it’s just exhilarating to sit in a darkened theater watching movie stars.

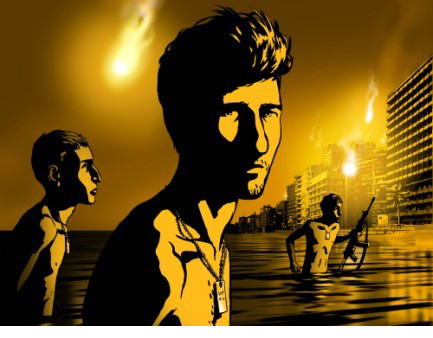

From the opening moments of marauding, snarling dogs to the final harrowing wails of widows, the animated documentary “Waltz with Bashir” is a thunderbolt, visually and emotionally provocative, arresting and riveting.

From the opening moments of marauding, snarling dogs to the final harrowing wails of widows, the animated documentary “Waltz with Bashir” is a thunderbolt, visually and emotionally provocative, arresting and riveting. The illusionist Buck Howard, played with relish by John Malkovich and inspired by The Amazing Kreskin, scaled to the summit of his career during the age when ventriloquists and plate spinners had a prominent place on prime-time television. In the 1970s, talk shows were still synonymous with variety shows and the last vestiges of vaudeville and cabaret found a spot on the bill. Presently, he boasts loudly that he was a guest 61 times on “The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson,” eager to add that he never graced the telecast when the inferior Jay Leno hosted; the irascible Buck, who won’t deign to call himself a “magician,” conveniently conceals that his last appearance on Carson’s couch was a decade before Jay debuted.

The illusionist Buck Howard, played with relish by John Malkovich and inspired by The Amazing Kreskin, scaled to the summit of his career during the age when ventriloquists and plate spinners had a prominent place on prime-time television. In the 1970s, talk shows were still synonymous with variety shows and the last vestiges of vaudeville and cabaret found a spot on the bill. Presently, he boasts loudly that he was a guest 61 times on “The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson,” eager to add that he never graced the telecast when the inferior Jay Leno hosted; the irascible Buck, who won’t deign to call himself a “magician,” conveniently conceals that his last appearance on Carson’s couch was a decade before Jay debuted. If only every movie had the director delivering his DVD commentary once the house lights come up.

If only every movie had the director delivering his DVD commentary once the house lights come up. On a family trip in the mid 1980‘s, we took the London to Edinburgh line and met a young Swedish couple. While the woman in her early 20s was attractive, she was routinely so, but in the post Borg age, when Edbergs, Wilanders, and Jarryds made such a racket, it was her companion with his preposterously perfect feathered hair, flawless English and effortless friendliness who my teenaged self and younger sister engaged in casual, convivial conversation as he poured Smarties into our hands.

On a family trip in the mid 1980‘s, we took the London to Edinburgh line and met a young Swedish couple. While the woman in her early 20s was attractive, she was routinely so, but in the post Borg age, when Edbergs, Wilanders, and Jarryds made such a racket, it was her companion with his preposterously perfect feathered hair, flawless English and effortless friendliness who my teenaged self and younger sister engaged in casual, convivial conversation as he poured Smarties into our hands. Diego Maradona, the coked up little genius of world football, was an artisan and a renegade and nowhere did his penchant for sporting sublimity and personal self destruction flourish more than in Napoli. The scruffy, diminutive El Pibe de Oro (the Golden Child) won a World Cup for Argentina in 1986 but the next year he accomplished something even more transcendent for his club side, SSC Napoli, by winning if not single handedly then with singular indefatigability the 1987 Serie A title. It was the first championship ever won by a southern Italian team after almost a century of competition, an historic moment with ramifications more far-reaching than the confines of a football pitch. The tifosi adore the skewed virtuoso with the low center of gravity and a high tolerance for the bacchanal even though he left the club, disgraced, in 1991.

Diego Maradona, the coked up little genius of world football, was an artisan and a renegade and nowhere did his penchant for sporting sublimity and personal self destruction flourish more than in Napoli. The scruffy, diminutive El Pibe de Oro (the Golden Child) won a World Cup for Argentina in 1986 but the next year he accomplished something even more transcendent for his club side, SSC Napoli, by winning if not single handedly then with singular indefatigability the 1987 Serie A title. It was the first championship ever won by a southern Italian team after almost a century of competition, an historic moment with ramifications more far-reaching than the confines of a football pitch. The tifosi adore the skewed virtuoso with the low center of gravity and a high tolerance for the bacchanal even though he left the club, disgraced, in 1991. The infobahn is atwitter with “Twilight.” While the North American box office nears $200 million and the world-wide figures double that return, and stories abound of behind-the-scenes intrigue with machinations so rabid that the director has been excised from the sequel and a third film has already been marked on calendars for 2010, the clamor can’t conceal that this vampire movie is a trifle, an unremarkable film so slight that random episodes of “Buffy” bustle with more humor, charm, wonderment, and, most importantly, verve. Catherine Hardwicke has directed a film without magic or vitality, fatal exclusions for a fantasy flick.

The infobahn is atwitter with “Twilight.” While the North American box office nears $200 million and the world-wide figures double that return, and stories abound of behind-the-scenes intrigue with machinations so rabid that the director has been excised from the sequel and a third film has already been marked on calendars for 2010, the clamor can’t conceal that this vampire movie is a trifle, an unremarkable film so slight that random episodes of “Buffy” bustle with more humor, charm, wonderment, and, most importantly, verve. Catherine Hardwicke has directed a film without magic or vitality, fatal exclusions for a fantasy flick.  When Liam Neeson lays siege on Paris, he transforms the capital into “The City of Lights Out.”

When Liam Neeson lays siege on Paris, he transforms the capital into “The City of Lights Out.” Not all films have to be the cinematic equivalents of novels, hulking celluloid tomes tipping the three-hour mark, so distended they should be fatted with an intermission. Some are poems. Two years ago, “Old Joy,“ a film meager in budget and a mere 76 minutes long, emerged, like the two reacquainted buddies and protagonists who spend a weekend in the Oregon woods, as a thoughtful meditation on friendship renewed, reviewed and ultimately reconciled as something lost from the kinship of youth. It cleverly steered clear of pretentiousness when insufferableness seemed unavoidable. Kelly Reichardt, the director of the resonant “Old Joy,” has returned with “Wendy and Lucy,” a movie chronicling the plight of a young woman ensnared in spiraling circumstances. But regrettably, the new, slight film is a vague and incomplete cinematic missive; Reichardt and co-writer Jonathan Raymond have scripted a haiku of 16 syllables.

Not all films have to be the cinematic equivalents of novels, hulking celluloid tomes tipping the three-hour mark, so distended they should be fatted with an intermission. Some are poems. Two years ago, “Old Joy,“ a film meager in budget and a mere 76 minutes long, emerged, like the two reacquainted buddies and protagonists who spend a weekend in the Oregon woods, as a thoughtful meditation on friendship renewed, reviewed and ultimately reconciled as something lost from the kinship of youth. It cleverly steered clear of pretentiousness when insufferableness seemed unavoidable. Kelly Reichardt, the director of the resonant “Old Joy,” has returned with “Wendy and Lucy,” a movie chronicling the plight of a young woman ensnared in spiraling circumstances. But regrettably, the new, slight film is a vague and incomplete cinematic missive; Reichardt and co-writer Jonathan Raymond have scripted a haiku of 16 syllables.