Please visit the newly redesigned One Film Beyond site which sports among its updates an improved, easy-to-navigate archives page for reviews and the weekly Beyond the Reel posts.

Archive for May, 2009

Beyond the Reel 8

May 22, 2009Coming in August. Quentin Tarantino’s Summer Blockbuster for the Indie World.

The divisive Lars von Trier returns with his latest contentious work, “Antichrist,” and Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times plays devil’s advocate as he pens a thoughtful essay on the film and the divergent reaction to the Danish enigma, which can be summed up by an enthralled First Showing’s Alex Billington exclaiming I had a blast watching this while Todd McCarthy of Variety says the auteur cuts a big fat art-film fart.

Opening on July 17, the postmodern, bittersweet love story “(500) Days of Summer” stars the adorable pair of “The Lookout”‘s Joseph Gordon-Levitt and “Tin Man”‘s Zooey Deschanel.

Kenneth Turan of the LA Times revels in Jane Campion’s “Bright Star” poetry while the New Zealand Herald’s Helen Barlow lauds the film as “Campion’s poetic comeback.”

One Film Wonder: “This is Spinal Tap” — the greatest mockumentary ever made — boasts not one but two one film wonders. David Kaff played the band’s loopy keyboardist, Viv Savage, and in the subsequent quarter century he has landed a half-dozen roles, mostly on Aussie telly. As the band’s latest ill-fated drummer, R.J. Parnell portrayed Mick Shrimpton with ciggy-dangling-from-the-lip rock and roll insouciance. Parnell was summarily typecast in his only other role; he was “Drummer” in 2004’s “The Devil’s Due at Midnight.” In Spinal Tap’s uproarious final credit sequence, both Savage and Shrimpton impart their succinct philosophies.

“The Class”: Haute for Teacher

May 22, 2009“The Class” is a lesson in adroit filmmaking.

Set in a Parisian working-class neighborhood collège, the film spends an absorbing year in the French language class of Mr. Marin. The portrait of an ethnically-diverse classroom of 14 and 15 year-olds in the American equivalent of late middle school is unsentimental and extremely forthright. Affixed with a purposely unassuming title, the film, based on a 2006 novel, is a thoughtful, engrossing study of daily classroom dynamics. There’s no grand statement or powder-keg denouement. Essentially, “The Class” is a Year in the Life motif that is plausible and compelling (so it’s filled with both familiar and new) without resorting to dubious histrionics or pyrotechnics. Director Laurent Cantet clearly knows the crucial difference between the dramatic and melodramatic; thus, he makes the ordinary absorbing.

Like so many Western European nations, France is burbling with concepts of national identity as more international travelers make their homes in a new, more unified Europe. Marin’s roll of students is filled by the children of immigrants from countries such as Mali, Morocco, Algeria and China and the topics of identity and assimilation course through almost every class project. Young but still an experienced teacher, Marin understands that these are core issues to his pupils, even if they aren’t consciously aware of their importance. (A parent-teacher night montage underscores the salient topic.)

Played by François Bégaudeau, Marin moves with ease through the rows of desks in his H&M inspired attire, chiding and cajoling for answers and insight, yet not with desperation. He is attractive, probing and no-nonsense but with a touch of arrogance, which suggests pride before the fall semester. Begaudeau — who penned the novel and co-wrote the screenplay – excels in his first film role. (Like Ryan Gosling in “Half Nelson” there’s an unaffected quality to this teacher, though none of the demons of Dan Dunne.)

Most of the two dozen students are portrayed by first-time actors who demonstrate a keen knack for unpretentious performances. When Marin presses for reactions to his inquisitive questions, the responses have a natural tenor. The neophyte cast nicely captures the way kids test a teacher, even one with Marin’s moxie, figuratively pushing and prodding to take control while the film also displays how teens can pivot from indifference to outrage (and back again) in an instant. It feels and sounds authentically like an actual classroom mixture of cocky and shy, outspoken and introverted young teens. At times, there’ a cacophony of backchat, but it’s not cluttered.

This is because Cantet oversees a film which feels both loose and controlled. The camera work by Pierre Milon scans the class with a documentarian’s intimacy but there’s no theatrical flitting. Editor Robin Campillo, who also co-wrote the screenplay, is equally focused and measured.

“The Class” also delves into the backroom machinations of the school. Marin is a reserved observer in a teachers’ lounge fraught with frustration over difficult students. He also serves on several school committees and the film cleverly and understatedly showcases how a serious committee discussion regarding discipline devolves into a silly debate about coffee machines. A disciplinary hearing also becomes a farce because a parent is not furnished with a translator while spoken to with the tippy-toed obsequious tone of administrative babble.

“The Class” doesn’t lecture as much as it observes. So the film ends ambivalently, like all school years, neither a conclusion nor a beginning, just with a bit of wisdom parsed out.

Beyond the Reel 7

May 15, 2009

Ooh. Aah. Cantona. The French footballing legend provides philosophical succor to a Mancunian postman in “Looking for Eric,” a new comedy from Ken Loach opening in U.K. theaters next month.

While Terry Gilliam presents The Imaginairum of Doctor Parnassus” at Cannes, exciting word arrives that his ill-fated, infamous Don Quixote project has found new life.

Arriving in US theaters next month, “Dead Snow” is the Norwegian comedy horror flick where students on holiday find their camping trip interrupted by gold seeking Nazi zombies.

David Gritten of the Telegraph chronicles “Fish Tank” director Andrea Arnold, whom he coins a well-kept British secret

One Film Wonder: O Romeo, Romeo, wherefore art thou Romeo? Well, we’re not sure really. But in 1968, a limpid 17-year-old Leonard Whiting swooned with Olivia Hussey as the titular tragic teens in Franco Zeffirelli’s attractive, romping “Romeo and Juliet.” A half-dozen TV films and a bit of musical work followed — including vocals on an Alan Parsons Project album — as Whiting’s show business career faded. But Whiting and Hussey still resonate as one of film’s most enduring pair of star-crossed lovers.

“Star Trek”: Champagne Supernova

May 15, 2009

A week after the dismal “X-Men Origins: Wolverine” dragged its sad carcass to the top of the box office heap, the much-anticipated, hyper-publicized “Star Trek” soars to the pinnacle of the charts as a massively entertaining, triumphant spectacle.

J.J. Abrams is no stranger to a rabid fanbase. Yet even the zeal of the “Alias” and “Lost“ devotees wouldn‘t have prepared the director for the onslaught from Trekkies if he‘d gotten it wrong. Trouble with Tribbles, indeed. And because the franchise is considered such a niche, the average filmgoer would have given a new underwhelming flick in the series no more than a passing glance. But Abrams has allayed any fears. He has crafted a film which will captivate a wide swath of folks, from the neophyte — say someone who only knows Avery Brooks from “Spencer for Hire” — to the fluent Klingon linguist.

Abrams has executed a dexterous balancing act. There is a respectful nod to the past, with a wink at times, but the film is clearly modern. The tone found between instances of humor and drama feels right and the pace clicks along briskly. The detailed backstory is understandable as much of the film intercuts across time, locations, and story arcs as the young crew meet and train at Starfleet Academy while an impeding Romulan menace gathers. Ultimately, the forces of the USS Enterprise and the Narada engage in a final, pulsating confrontation. (There’s quite a bit more happening than that but it’s not fair to play the spoiler.) The script by Roberto Orci and Alex Kurtzman straddles the lighter moments and the instances of pathos with alacrity.

It doesn’t take long to decipher that “Star Trek“ is a confident prologue to the Star Trek saga. An enthralling opening sequence set on the doomed USS Kelvin which reveals the circumstances of Kirk’s birth and the fate of his father is tight, stirring and heartrending.

Technically, the special effects are stupendous, especially the intricate ships and palpitating space battles. The cinematography from Dan Mindel is equally strong in space and on the ground. And a fight sequence with the newly graduated Kirk and Sulu skydiving onto a floating laser drill is riveting and highlights the stellar editing by Maryann Brandon and Mary Jo Markey. Costume designer Michael Kaplan creates costumes that are familiar but subtlety updated.

While the film has serious sci-fi chops and dire situations, “Star Trek” doesn’t overlook the comedy inherent in the original inspiration. So along with breezy, witty banter, we find Kirk macking with a green-skinned lady, an exasperated Bones punctuating almost every declaration with “Dammit” and Scotty declaring that he can’t hold it much longer. (It also discloses an unexpected romance.)

With a cast of newcomers and familiar faces, characters are given fresh, valid interpretations. Chris Pine is a blast as the brash James T. Kirk. Zachary Quinto is well known as Sylar on “Heroes,” and he completely nails the part of Spock, which must have been one of the more intimidating attempts in recent years. Quinto’s assured portrayal of the taciturn Vulcan-Human is highlighted in his scenes with Leonard Nimoy, who makes an admirable cameo. Zoe Saldana struts beguilingly as Nyota Uhura while Karl Urban convincingly pouts as Dr. ‘Bones’ McCoy. Once aboard the revamped Enterprise, both John Cho of “Harold and Kumar” fame as Hikaru Sulu and Anton Yelchin as Pavel Chekov deliver strong personas. The winsome Simon Pegg clearly has the time of his life as Scotty. An almost unrecognizable Eric Bana erupts as the vengeful rogue Romulan, Nero. (It’s a nice touch that an ancillary role like Ayel, Nero’s second in command, is cast with the talented Clifton Collins, Jr.)

“Star Trek” is an impressive feat. It has vanquished all doubts and raised expectations for the next chapter. And it might be difficult to lure Abrams back to a deserted South Pacific island when he can explore strange new worlds across the galaxies.

“Hunger”: Belfast and Furious

May 15, 2009

I

All you punks and all you teds

National Front and natty dreads

Mods, rockers, hippies and skinheads

Keep on fighting ‘til you’re dead

Who am I to say?

Who am I to say?

Am I just a hypocrite?

Another piece of your bullshit

Am I the dog that bit

The hand of the man that feeds it?

Do the dog, do the dog

Do the dog, not the donkey

Do the dog, don’t be a jerk

Do the dog, watch who you work for

Do the do the do the do the dog

Everybody’s doing the dog

Take your F.A. aggravation

Fight it out on New Street Station

Master racial masturbation

Causes National Front frustration

Who am I to say?

To the IRA

To the UDA

Solider boy from UK

Am I just a hypocrite?

Another piece of your bullshit

Am I the dog that bit

The hand of the man that feeds it?

II

In the spring of 1981, I wore out the grooves on the first of many copies of The Specials debut album. The second song on side one is the infectious “Do the Dog.” Opening with an insistent wall-of-sound drumbeat, the tune fast becomes a skanking bop. But in the tradition of so much ska and reggae, the cavorting sounds mesh with socially pertinent lyrics, a volatile tale of man-made madness surging from Downing Street to war in a Babylon.

The year proved pivotal for director Steve McQueen, who in his first full-length feature film, the profound “Hunger,” chronicles the Maze Prison during the final months in the life of the Irish Republican Army’s Bobby Sands. As noted by Boston Globe journalist Christopher Wallenberg,

1981 is a year that British artist Steve McQueen will never forget, with the Brixton riots erupting in South London and his favorite soccer team, Tottenham, winning the FA Cup. But what he recalls most vividly about that time is sitting at his home in West London as an 11-year-old and watching disturbing news footage flow from the television set. Night after night, an image of a man with a number under his face glowed on the screen, and the number kept escalating with each passing day: 56 . . . 57 . . . 58. The number, McQueen learned, represented the total days since the man had last eaten while on hunger strike at the notorious Maze Prison in Northern Ireland.

III

An artist working most commonly in film since the early 1990s, Steve McQueen won the Turner Prize in 1999. The centerpiece of his Turner collection was “Deadpan,” a 4-minute twist on the Buster Keaton bit where a wall from a barn-like structure crashes around McQueen as a large window cutout passes around his body. In his book on young British artists, “High Art Lite: British Art in the 1990s,” – which Ana Finel Honigman calls “an excoriation of the pop posturing beneath the yBa’s punk exterior” – Julian Stallabrass underscores that McQueen the artist is distinct from many of his contemporaries.

“His slow, hypnotic films, shot from strange angles – echoing early modernist innovations – and showing odd, sometimes ritualistic actions, leavened with issues of race, are a world away from high art lite.”

IV

In 2002, Steven McQueen made “Western Deep,” a 25-minute documentary style film which delved into the suffocating pit of a South African goldmine. He spoke to Libby Brooks of The Guardian about his objective for the audience.

“I’m throwing you right in at the deep end and you have to make your way. That gives people their own power because they are making sense of it by themselves, not being told.”

V

“Hunger” is a primal experience. McQueen retains that languid, hypnotic style. The film begins with very little dialogue as he composes small, delicate impressions: snowflakes on a bruised knuckle; a fly darting over fingertips stuck through a barbed window; and jail cell walls smeared in feces with artistic swirls. Deprivation and melancholy become tactile.

VI

McQueen empowers the audience by quickly documenting political prison life; the furtive transfer of contraband; the fetid blanket and bathing protests; and the violent reaction to dissent. (Perhaps it is not surprising that when a person is deprived, they use their food, their shit, their piss, their nakedness — their very essence — as weapons of disobedience.) Filmed with appropriate bluntness, the scenes of torture and brutality are unflinching.

VII

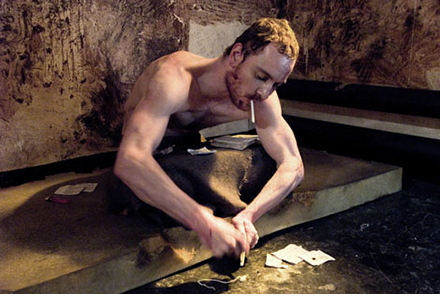

“Hunger” is reflectively visceral. So when Bobby Sands and Father Moran debate the principles of the hunger strikes in the film’s astounding centerpiece scene, it pierces the movie with brute force. Sands has invited his priest to the prison. But this is no confessional. Filmed in distant profile with the two sitting across from each other at a small table in a bare, antiseptic visitor’s room with diffuse light cutting through frosted windows, Sands and Moran battle verbally. That initial shot is held for no less than 10 minutes. Again, McQueen’s decision thrusts the viewer into the core of the conversation. Without the benefit of edits and varying camera angles, the attention to detail is in the words. Scripted by McQueen and playwright Enda Walsh, the dialogue doesn’t sound like a playwright’s fancy; it’s a defiantly genuine tussle. Michael Fassbender is unretractable steel as Sands while Liam Cunningham is forthright and impassioned.

VIII

The weight loss Fassbender endures for the role is unsettling and not made any easier to digest knowing he was supervised closely by a medical team during the filming. Known most readily for his sly turn as the best thing in the BBC supernatural series “Hex” and also familiar for his role as one of the strapping Spartans in “300,“ he delivers a transfixing and revelatory performance. Fassbender loses a massive amount of weight and the images of a painfully thin Sands in the prison infirmary in his last days are not easy viewing. Like Christian Bale in “The Machinist,” the performance does foment a debate about the extent an artist should go in their quest for realism in a portrayal.

IX

In 1995, McQueen made the short film “Five Easy Pieces.” In one portion of the film, he pisses directly into the camera. Mark Durden recalls in Parachute magazine that McQueen had been quoted as saying, “I wanted a situation where I was peeing while people, the audience, would be under me as it were — the dynamics of that situation.”

In “Hunger,” thankfully, McQueen has refrained from that youthful urge to purposefully antagonize. As a debut director, he has demonstrated a perceptive ability to refrain from the overly manipulative or the strident. Instead, he has molded an emotive subject into a meditative piece where the viewer can determine that the cloak of culpability covers all.

A Movie for Mother’s Day

May 10, 2009

Dear Mum,

I remember the first time we watched “The Ladykillers.”

For so long it was one of those Ealing Comedies you never expected to see on American television. But one day we happened upon it on the WGN schedule, and even though the copy was a bit worn, the brilliance of the 1955 comedy classic shone through.

Directed by Alexander Mackendrick, “The Ladykillers” is the perfectly executed caper of five bank robbers posing as a string quintet whose plans for an ingenious heist go horribly awry with the unwitting interference of their genteel landlady. I know that it has a special resonance for you because it captures a familiar street view of the post-war London of barrow boys and the last vestiges of rationing from your youth.

A story of exquisite simplicity chockfull of the screwball and the macabre, the film has haplessness and coincidence combining to conspire to foil the five. (As a bogus quintet they have to throw a record on the turntable, but in an inspired comic touch, they only have a single recording. For days afterwards, Boccherini’s Minuet burrows in as a melodious earworm.) The script by William Rose, who said that he visualized the entire plot in a single night’s dream, was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay.

The cast is tremendous. Alec Guinness slinks about as the thieves grotesque mastermind, Professor Marcus. The rest of the gang are a casting director‘s tour de force: Peter Sellers in his first breakout role as Harry, the jittery Teddy Boy; Danny Green as the kindhearted giant “One Round;” Herbert Lom as the oily, suspicious Louie; and Cecil Parker as urbane Major. But special mention must go to Katie Johnson as Mrs. Wilberforce. She reportedly was passed over initially for the part because of fears that she was too old and may not survive the filming. (A younger actress was cast; she died before filming commenced.) The film is buoyed by cameos from comedians such as Frankie Howerd and Kenneth Connor.

Two years later, Mackendrick directed the dark, atmospheric American classic “Sweet Smell of Success,“ which is especially laudable for James Wong Howe’s evocative black and white photography and penetrating performances from the formidable Burt Lancaster and the exquisite Tony Curtis. Amazingly, Mackendrick directed his last film in 1967. He left the industry, as Patricia Goldstone has written, after he “found himself spending more energy on making deals than on making films,” and taught filmmaking at the California Institute for the Arts for the next 25 years.

Since that first viewing we’ve seen “The Ladykillers” several times. Invariably, I’m grinning the whole way through, smiling in the moment while awaiting those particularly cherished scenes. Here is the original trailer for “The Ladykillers.” It doesn’t include our favorite line. (That’ll remain our oft-quoted joke.)

“The Ladykillers” is a great film and whenever I think about it I think about you and how much I love you.

Happy Mother’s Day,

Matthew

Beyond the Reel 6

May 8, 2009

Gael García Bernal and Diego Luna have teamed up as professional footballers in “Y tu mamá también” screenwriter Carlos Cuarón’s sibling rivalry comedy “Rudo y Cursi.” In the film, Bernal performs an uproarious cover of Cheap Trick’s “I Want You to Want Me.”

Steven Soderbergh chats about “The Girlfriend Experience” with Time Out New York while he talks to Mike Scott of the Times Picayune about the new call-girl in-the-digital-age film and his next project, “Moneyball,” the baseball biopic led by Brad Pitt.

Starring Michelle Pfeiffer in the titular role as a courtesan in 1920s Paris, “Cheri” is the esteemed Stephen Frears latest work, opening next month.

Film International is Slumdogging It.

One Film Wonder: On the shortlist of any greatest action film debate, “The Road Warrior” (or “Mad Max 2” as it was known everywhere except the States) is one of the true plunk-down movies. (To determine a film’s plunk-down status, just flip around the dial and stop on a film. If you plunk down on the couch and haven’t moved in the next 80 minutes, it’s an all-timer.)

George Miller’s 1981 followup to “Mad Max” checks every box for an amazing action movie. A fully actualized world, a wasteland steeped in atmosphere. A gorgeous, cynical anti-hero. Authentic punks. Just the right dose of humor. Kick ass driving stunts. A boomerang wielding Feral Kid…Mel’s leather pants. And a chilling chief villain, The Humungus. Ripped from the stage of a post-apocalyptic Joe Weider competition, the masked, leather clad philospher-cum-psychopath was authentically intimidating. The Humungus was played by Kjell Nilsson, a Swedish weightlifter who moved to Australia to train Olympic athletes preparing for the Moscow games. He was cast in only three other projects; in 1984 he played a “male nurse” in the Australian made for television film, “Man of Letters.” Here “The Ayotollah of Rock n’ Rolla” delivers his final ultimatum in a scene which has almost everything…even Mel’s leather trousers.

“X-Men Origins: Wolverine”: A Glutton for Punishment

May 6, 2009

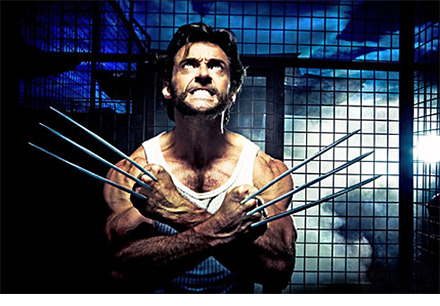

In a land where every dinner is a TV dinner and people watch remotely, “X-Men Origins: Wolverine” will mollify the packs of Nielsens swooping down on America’s megaplexes.

But the first movie to christen the blockbuster season is a long 107 minutes of nothing special. With an estimated $150 million budget, the producers have concocted to make a quite unspectacular popcorn flick. When a film is endowed with such a massive expenditure as “Origins: Wolverine” one wonders where the money went when compared to the sardonic rush of “Iron Man” or the fully-realized macrocosm of “The Dark Knight,” because it’s an uninspired project void of the magic of those franchise foundries. Perhaps when you’ve dropped this magnitude of an exorbitant investment into a tepid film, producers are forced to tack on an ambiguous and presumptuous conclusion suggesting a wholly underserved sequel.

Essentially a prologue to the X-Men films, “Origins: Wolverine” begins with the backstory of the Logan/Wolverine character and his brother, Victor Creed/Sabretooth, as children in the 1840s Antebellum South. They bound through successive U.S. wars as indestructible soldiers during the mundane opening credits until they are recruited into a post-Vietnam War commando unit. Adopting distinct military tactics, the brothers become estranged, each hunting the other until the inevitable last reel.

Filmed unconvincingly by director Gavin Hood, it’s an untextured effort with no discernible cohesive tone or pace. Action sequences are neutered by the special effects. The over reliance in post-production fiddling means that real thrills and genuine tension are jettisoned for clunky, newfangled visuals.

The lame script by David Benioff and Skip Woods is equally lackadaisical but there are moments when it’s just plain infantile. As he stalks his lumberjack younger brother in the Canadian Rockies, Victor scrawls with his fingernails into the wooden bar of a dark, unpopulated tavern in the middle of nowhere that for no apparent reason is the size of a jumbo jet hanger. The quizzical bartender asks Victor, “You’re not from around here?” Moments later, when Logan enters the bar, Victor peers over his left shoulder and drawls, “Look what the cat dragged in.” As the brothers race towards each other in the cavernous watering hole and begin to engage in battle, the barkeep peeps up with “Guys, take it outside.”

Burdened by the soporific screenplay, the game cast plows through. Bravely sporting mutton chops throughout history, Liev Schreiber lends Victor hubris with a perverse glint. Danny Huston, looking like a short back and sides Anthony Bourdain after a summer of prix fixe dinners, adds a trenchant interpretation to the commando unit chief, William Stryker, but like his co-stars is encumbered with dopey dialogue. Ryan Reynolds enhances his reputation as a funny fellow with a smart-alec turn as commando Wade Wilson, yet when he returns later in the film as Deadpool, a mutated government project, he is muted with bandages and stitches. (The film hints at the mutant’s irony; just maybe not the one the makers intended.)

Brooding, with trapezius muscles inflating with every swipe of his rapier hands, Hugh Jackman certainly put the requisite hours in the gym. But the character is written so rudimentarily that there’s no connection to his tortured plight. In several instances, Logan expresses himself with a vengeful cry to the heavens as the camera bids a clichéd retreat into the clouds. But at the very least the perpetually tank topped and frequently shirtless Jackman could bring hairy back into vogue. While his charm and charisma are rarely utilized to their best in this film, he has the affable hunkiness to play a part like Thomas Magnum. You can envision a mustached Jackman beaming behind the wheel of a Ferrari. (May I suggest William H. Macy as Higgins.) Again, a big screen presence for small screen tastes.

Beyond the Reel 5

May 1, 2009

Opening this weekend on a limited basis before fanning across the country, “The Limits of Control” is the latest flick from the mercurial but always salient Jim Jarmusch. Appearing in the pivotal role of Lone Man is Isaach De Bankole, who starred with Alex Descas in the laconic No Problem vignette from the wonderful “Coffee and Cigarettes.”

In the May issue of Sight and Sound, Ginette Vincendeau commemorates the 50th anniversary of the French New Wave by observing the movement’s transmutating influence on The Star Reborn.

At the hazy dawn of an early morning in 1976, the prolific director Claude Lelouch buckled up and without a permit roared through the streets of Paris filming an uninterrupted eight-minute thrill ride that’s become a Gearheads classic. It was madly dangerous. (He’s copped to the recklessness.) But “Rendezvous” is breathtaking. And mesmerizing.

Following a 15-year self-imposed exile from directing since the notorious “Boxing Helena,” Jennifer Lynch shares a frank and sometimes peculiar exchange with Time Out London about the the 1990s critical beatdown, her father’s influence and the genesis of the new film, “Surveillance.”

One Film Wonders: Vittorio De Sica’s “The Bicycle Thief” is a film of overwhelmingly powerful emotional potency. Much of the film’s poignancy resonates from the performances of Lamberto Maggiorani as Antonio Ricci and Enzo Staiola as his son, Bruno. They were both non-actors when each was cast in this first film role — Staiola reportedly was chosen for his distinctive walk. In the next 20 years, Maggiorani snagged unassuming parts in 15 films with ungracious character names such as “lonely patient” and “poor man.” Staiola would recede in the subsequent 30 years into anonymous roles as well with monikers like “newspaper seller’s son” and “busboy.” But as this sequence in a restaurant so vividly demonstrates, the novices effortessly express a wealth of emotions as cinema’s most sublime father-son duo.