Two years ago, a mere sliver of a movie slipped into theaters. And while “The Puffy Chair” snared a scant $194,000 at the box office, in Portland, it camped out for months on end as the genuine, modest tale of a gently undulating road trip to deliver a birthday present LazyBoy persistently charmed with its unpretentious and heartfelt relationships.

Two years ago, a mere sliver of a movie slipped into theaters. And while “The Puffy Chair” snared a scant $194,000 at the box office, in Portland, it camped out for months on end as the genuine, modest tale of a gently undulating road trip to deliver a birthday present LazyBoy persistently charmed with its unpretentious and heartfelt relationships.

The film became attached to the burgeoning Mumblecore movement yet, contrary to that name, it possessed clearly enunciated characters and had a wealth to say about familial interaction. The Duplass brothers, Jay and Mark, have returned this summer with “Baghead.” And while they’ve made a film distinctly different in plot as they have replaced a road trip movie with a slasher film satire, the meagerly budgeted “Baghead” still contains real, relatable characters who hold our interest as they fumble through a mélange of predicaments. Most of these dilemmas are distinctly small and human, while as the film unfolds they become ones faced universally by folks stranded in the woods at the whim of a homicidal spectre. “Baghead” could have been subtitled “Nightmare on Emo Street.”

Four struggling actors venture to the woods with the hope that the getaway will inspire them to write a script for their own film. Matt (Ross Partridge) and Catherine (Elise Muller) are an on-again, off-again late 30s couple trying to figure out if there’s something more to their “friends with benefits” arrangement. Chad (Steve Zissis) is the portly, funny guy who pines for Michelle (Greta Gerwig), who appears to be channeling Chloe Sevigny as a sorority girl.

As the creative process blends into card games and bullshit sessions, they chat in realistic broken sentences, speaking over each other in a natural, conversational way. There is a normality to the way they express their self-esteem doubts and qualms of self confidence. The riffs are amusing and the humor emanates effortlessly. Zissis is particularly notable for ensuring that his character isn’t a tired cliché. It’s no shtick and he illustrates terrific range.

When the film ventures into the slasher film elements, “Baghead” retains its shape. Clearly, there’s less talk, more running. But the video camerawork doesn’t become jarring. It’s active without being wonky. And if you suspend belief, the movie generates palpable suspense and legitimate thrills at the same time that it distracts from a deeper examination of the foursome’s rapport.

There’s little doubt that for some “Baghead” will feel quite slight. Plainly, they won’t be able to get past the frayed-around-the-edges quality. There’s a pronounced buzz in the sound, the lighting can appear dim and the set design is essentially non-existent. And a snarky wit could say that not only is the film set over one long weekend, but “Baghead” appears to have been shot over that same one weekend.

But in a movie-making world where a portly disaster such as “Evan Almighty” gorges on a $175 million budget, it is both heartening and dispiriting to remember that valuable films such as the $150,000 budgeted “Once,“ the equally modestly financed “Chop Shop,“ and the even more impecunious “Baghead“ are made for such infinitesimal amounts. To put a dollar figure on art, with that Almighty total you could make at least 1,750 “Bagheads.” Folks may agree to disagree on their overall quality, but small-budget films such as the enjoyable “Baghead,“ despite any imperfections, lend a crucial and clear voice to the screen.

As summer blockbusters churn out a succession of candy floss confectionary seemingly best viewed through 3-D glasses, “The Dark Knight” is storytelling so obsidian theaters should hand out night vision goggles.

As summer blockbusters churn out a succession of candy floss confectionary seemingly best viewed through 3-D glasses, “The Dark Knight” is storytelling so obsidian theaters should hand out night vision goggles.  The story begins at an ending, of sorts.

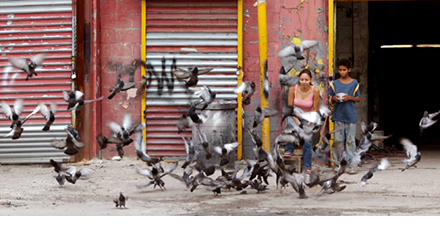

The story begins at an ending, of sorts.  In one corner of Third World America, where pigeons are pets, a 12-year-old boy in Queens scrounges for chop shops purveyors in the shadow of the Flushing Line as constant flights from La Guardia glide across the Willets Point sky like unobtainable mirages. It’s a life teeming with transportation for people going nowhere.

In one corner of Third World America, where pigeons are pets, a 12-year-old boy in Queens scrounges for chop shops purveyors in the shadow of the Flushing Line as constant flights from La Guardia glide across the Willets Point sky like unobtainable mirages. It’s a life teeming with transportation for people going nowhere.